Becoming a mother amid war in Ukraine

Two days after the birth of my daughter, Russia launched one of its largest air attacks on Kyiv. It was terrifying, but also entirely expected, and that's the worst part.

The sun had not yet come up in the early hours of January 2, when my husband and our one-day-old daughter, Ava, finally dozed off in their uncomfortable hospital beds. I tiptoed around the room looking for a change of clothes, diapers for Ava, napkins, some food, and water, putting everything into a backpack near the exit.

It was around five in the morning, and dozens of Russian missiles and drones were an hour away from Kyiv. I let everyone sleep for another 50 minutes. Then came the first explosions and we rushed to the bunker, along with dozens of pregnant women and babies who spent their first hours of life hiding underneath the Kyiv Perinatal Center because they were born near Russia.

In 2024, becoming a mother at 23 is a lonely endeavor. Most women wait until they hit 30 to have children, so many of your friends are likely to get lost in the shock of your motherhood and drift away. Some assume it was an accident. Some think you’ve gone crazy and tell you to your face that your career is ruined.

Becoming a mother in a war zone makes it exponentially worse: of course, there is the risk of your family getting killed, but there is also the awkward sympathy coming from those who’ve only seen war on screens. War, like motherhood, cannot be explained; it can only be experienced. The combination compounds the uniqueness of both experiences.

My name is Anastasiia Lapatina: I’m a Ukrainian journalist based in Kyiv and the Ukraine Fellow at Lawfare, a national security publication in Washington D.C. I am writing this in an attempt to mend the deep misunderstanding that exists between Ukrainians and the rest of the world. Everyday life in Ukraine is often unlike what you see in the news, and there are also different realities in other areas of the country. Mine is in Kyiv – the Ukrainian capital.

I always thought I’d be one of those women who diligently build their careers and settle down sometime after 30. I never wanted kids, until I met my husband in the summer of 2022. He joined the military on the morning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, and I paused my studies abroad to return and report on the war. We made for a dramatic couple.

One day, I opened a conversation about growing our family, knowing that we didn’t live in the greatest of times and places to make babies.

There were so many ridiculous things to consider.

We’d have to move to an apartment that wasn’t close to any military bases, ministries, or government institutions like the State Security Service, all of which are targets of Russian missile attacks. We also couldn’t live in certain areas of Kyiv which, as is publically assumed, harbor air defense systems; the explosions are much louder, and the risk of missile debris falling on your balcony is much higher. Apartments higher up than the third floor were a non-starter due to similar risks. So were the apartments that didn’t have gas in the kitchen, because we needed a stove that would work during a blackout. We also needed an underground shelter nearby (which you’d think is not an issue for a country at war, but it is; three years in, many housing complexes don’t have bunkers in their proximity).

And what do we do if things get worse in Kyiv? If Russians launch another offensive and the capital can’t hold, I’d need to move to the west of Ukraine or even abroad. But my husband, like nearly all husbands in Ukraine, can’t get out of the country. He is on active duty and goes on combat missions. What if he dies? What if the Russians take him as a POW? What if he goes missing? How will I take care of him if he is injured?

At one point, when we were still only engaged, my mother insisted that we not procrastinate on tying the knot – for all those worst-case scenarios, I needed to be his wife. The system had to recognize me as someone to whom it owes answers and help if something happens to him.

Despite a sharp 30 percent decrease from before the full-scale invasion, 187,387 babies were born in Ukraine in 2023. Our daughter was one of them.

She showed up on New Year's Eve, at 10:32 in the morning. And she didn’t show up alone. The morning of January 2 saw one of the biggest Russian attacks against Kyiv since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, with more than 60 missiles attacking the city.

I had been ignoring air raid sirens for more than two years, but all of a sudden, having just delivered a baby, my safety calculations had changed dramatically.

Like most Ukrainians, I had gotten so used to everyday air alarms that I could count on one hand how often I reacted to them. Alarms are triggered when Russian planes get up in the air, but they often do that for relocation or refueling, not just for attacks. There have been more than 1,150 air alarms in Kyiv since February 2022: that’s at least once every day. The absolute majority of air alarms don’t result in attacks, and it’s routine to hear one and see a cafe full of people or a playground full of children all staying put and acting like nothing is happening. It’s probably baffling the first time you see it, but it’s a rational behavior. Most air raids, after all, are not the ones that are going to kill you.

There are several government-run and anonymous channels on Telegram (the messenger app primarily used in Ukraine) that track the movement of missiles and drones, reporting when and how they are moving through Ukrainian airspace. So if a missile was heading towards Kyiv, I would be careful. Otherwise, I generally did nothing.

But on the morning of January 2, the Telegram channels were all going wild. Everyone who had any access to airspace information – from anonymous IT nerds to government officials – was pleading for people to be extra careful and take cover.

I gave birth at Kyiv’s Perinatal Center – the main maternity ward in the city, which specializes in emergency care for premature and otherwise difficult births. Apart from having the best specialists, it also has an impressive system of bunkers where any operation can keep going even amid a full blackout. That’s why we chose it.

As we started hearing booms in the distance, hospital staff encouraged everyone to get to the shelter. Ten minutes later, booms got louder and louder, and the encouragement became an order. But there was a problem: the bunkers were on the other side of the hospital, and the elevators were out. What’s worse, we had to go two floors up, then across a glass corridor connecting the two buildings, and then three floors down to get to the shelters. A glass corridor is not a good place to be during a missile attack.

And by we, I mean dozens of very pregnant women, women who had just given birth, husbands holding tiny newborns, and doctors who trying to keep things under control.

At this point, I could barely walk. I didn’t have the easiest of deliveries, so every step was

extremely uncomfortable. Adrenaline helped in numbing the pain, but several women with me might go into labor any minute, and I could not even bear looking at them because I was so traumatized by Ava’s arrival.

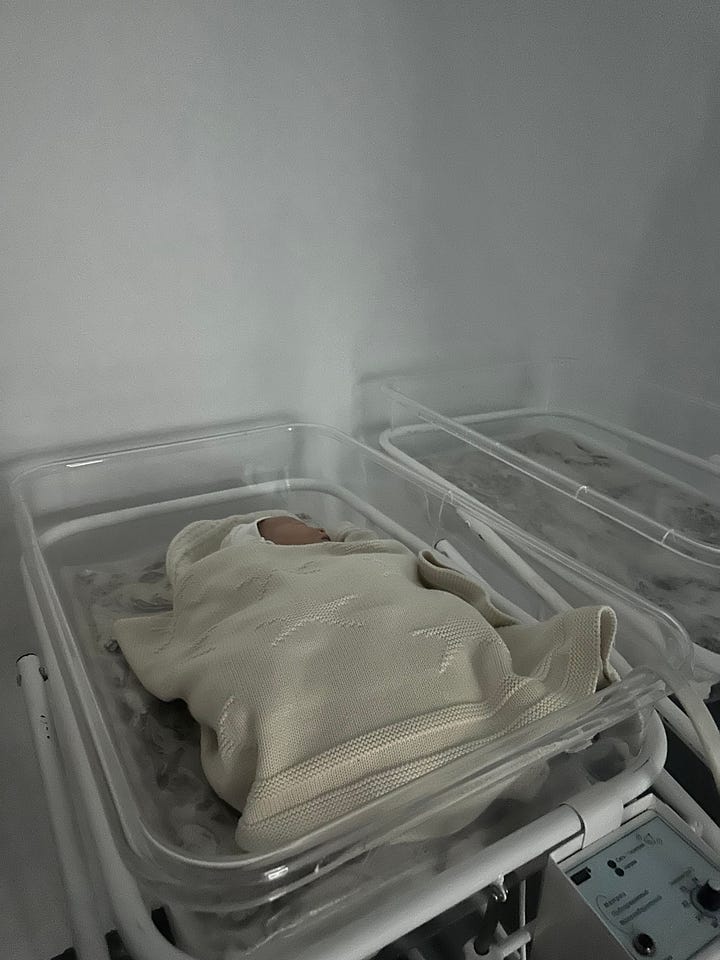

We finally reached the shelter, where crowds of women and men were taking cover. The shelter is a maze of dark cramped rooms with hospital cribs, chairs, and basic supplies for the newborns. We found a room occupied by a couple of similar age, whose baby was born a day earlier than Ava. For the next several hours, we shared anxieties, stories about our epidurals, and—at a more tangible level—makeshift breastfeeding pillows. Most importantly, we all shared the feeling of the deep fucked-upness of the whole experience.

“I should probably photograph this for history,” I thought.

What infuriated me most was that nobody seemed panicked. Nobody cried because they were scared. The doctors, the patients, and their loved ones all knew the drill. We all knew what to do and quietly followed instructions. We all must have imagined this scenario a dozen times over the previous nine months.

Did we pack emergency supplies? Did the hospital have enough generators? What if I needed to deliver my baby in an underground bunker? What if she had complications after that? Was the hospital prepared for a mass attack? We had been there before a hundred times in our minds.

This was the complete normalization of violence, the logical endpoint of the endless game of cat and mouse we always played with the Russian missiles trying to kill us. This game has become so routine and we have become desensitized to it, that of course it ended up in a maternity ward bunker just after delivery. We were barely afraid. We were just angry.

That morning was my most intense experience of this war, except for the night I spent in my hometown Kherson shortly after its liberation. (After a night of non-stop artillery, a grad rocket landed a few streets from us and shook our house. I kept imagining how the wooden ceilings would collapse right on my face and what it would feel like. Would I feel anything at all, or would it kill me immediately?)

We were underground but were still hearing explosions from Russian Kinzhals above us loud and clear. An hour later, social media was flooded with photos of the grey Kyiv skyline, large clouds of smoke rising all around the city. We gasped and swore. We called family members, texted friends, fed our newborns, and continued scrolling the news over and over for hours until it was over.

Four people were killed in and near Kyiv that day. But to Russia’s dismay, many more Ukrainians were born.

If you liked my first essay, please consider subscribing to Yours Ukrainian and share it with friends. That way I can keep writing more about life, culture, and politics in Ukraine, and build a close community.

Cheers, and Glory to Ukraine

—Yours Ukrainian

I so admire you and so many Ukrainian people. Stay steadfast. I am doing everything I can to make sure US elected officials give you strong support. Putin must be stopped.

Beautiful, brave, poignant writing! I never forget that every single written word, by Ukrainians and non-Ukrainians, for and about Ukrainian life, is a way to resist Russia. And also annoy Russia.

Thank you for taking time to write, and writing so thoughtfully, amidst electricity cuts, internet issues, sirens, bunker times, feeding baby, changing diapers, calming a fussy baby, playing with a happy, smiling baby, loving, loving, loving your precious little one. ❤️